The dynamics of the Indian retail market are evolving fast as consumers embrace new ways of shopping in tune with the ‘new normal’ in a pandemic-hit world. As digitisation has become the latest buzzword, offline trends are making inroads into the online world.

For many years now, offline retailers like the Future Group, Reliance Retail, K Raheja Corp-owned Shoppers Stop and the Aditya Birla Group have been betting on private labels (products contract-manufactured and sold by retailers) as these ensure higher profit margins and, therefore, healthy gross margins. But what used to be a lucrative business strategy for offline retail soon got replicated in the online world as a key arsenal to bolster growth. Over the past four-five years, the likes of Amazon, Flipkart, BigBasket and others are steadily launching their ‘own’ brands and scaling them up as these are a win-win for both consumers and retailers. They offer convenience, trust and better pricing for consumers and higher margins for retailers.

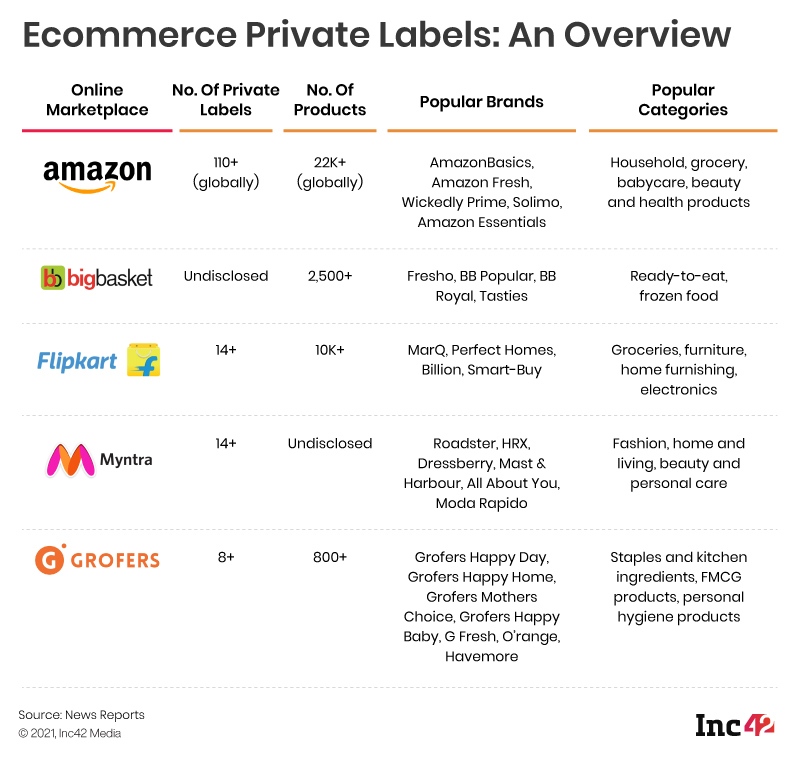

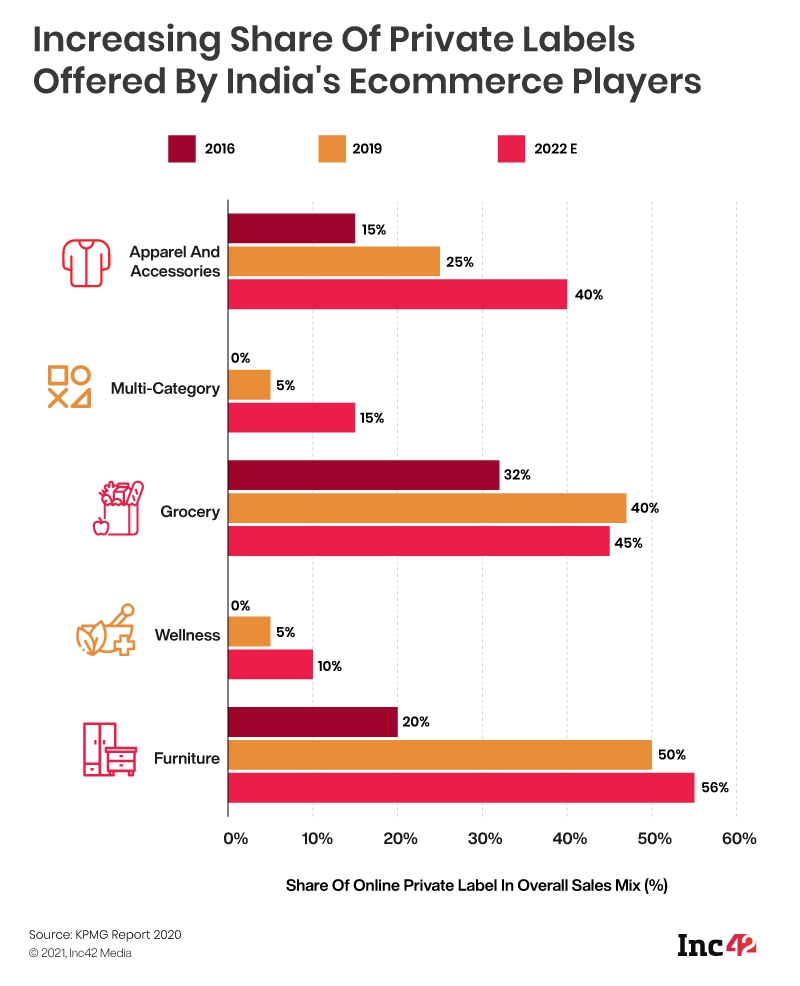

In 2016, Flipkart launched its first private label called Smart Buy, an umbrella brand that sells products across 30+ categories, including electronics and household goods. As of now, the Walmart-owned ecommerce behemoth’s private brands business covers more than 150 verticals, from groceries, furniture and home furnishing to electronics and more. Most of the ecommerce platforms have at least two-five private label brands in categories such as wellness, electronics and cosmetics, while larger categories like apparel and grocery have nothing less than 15-20 private labels, says a 2020 KPMG report on online private labels.

“If you look at any successful retailer globally, they have a pretty large and sustainable business of private brands across categories,” said Adarsh K. Menon, vice-president and head of private brands, electronics and furniture at Flipkart, in a blogpost. “Somewhere in the middle of 2016, as a leadership team, we sat down and looked at our business over the next 3-5 years. One of the many things that came out as an area of opportunity was the lack of a private brand business,” he added.

Last year, the group bought a minority stake in Aditya Birla Fashion and Retail (ABFRL) for INR 1,500 Cr to ramp up its fashion business and co-create new-brands in the segment. As for Flipkart-owned Myntra, its private labels such as Roadster, HRX and Anouk accounted for nearly 26% of its sales during the festive sale in October 2020.

Amazon India is also building a huge private-label business with brands like AmazonBasics, Solimo, Echo, Myx and others. Globally, the conglomerate can earn as much as $25 Bn in revenue by the end of 2022 from its private brands.

Bengaluru-based online grocery platform BigBasket is also betting big on private labels and seeing high growth. As of August 2020, around 38% of the company’s revenue came from its private labels — Fresho, Tasties, Royal and Popular. The egrocer now wants to push the sales to 45% with a whole range of new FMCG products.

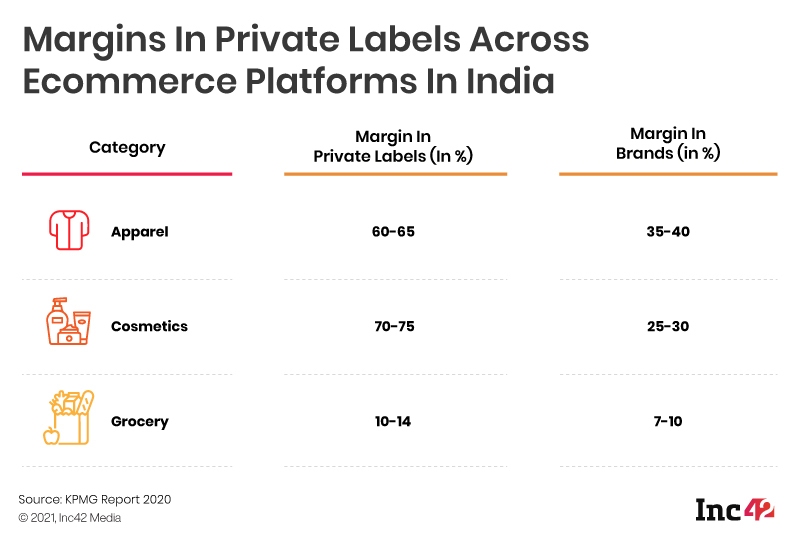

The categories where private labels are more prevalent include fashion, grooming and personal care, and food and beverages. According to the above-mentioned KPMG report, between 2019-22, these brands are expected to grow 1.3 to 1.6 times faster than the ecommerce platforms and will continue to generate 1.8x-2x higher margins than external brands sold by these online retailers.

Why Ecommerce In India Needs Private Labels

Ecommerce in India is as old as the current millennium, but the sector has gained momentum only in the past few years. However, these platforms have not been able to improve their bottom line by selling external/third-party brands alone. The reason: lower gross margins garnered from popular brands, high logistics costs and, most importantly, high discounting and marketing costs required to acquire and retain customers.

Hence, ecommerce platforms are betting big on private labels as the margins are comparatively better due to supply chain efficiencies and better control over operations. Moreover, margins can be defended against the competition through a loyal customer base, says Ankur Bansal, cofounder and director of BlackSoil, a venture capital firm that has invested in D2C brands like Bajaao and RapidBox.

An additional advantage of a private label portfolio is that ecommerce companies are able to work with multiple vendors across locations, unlike bigger brands who supply from centralised locations. This helps online marketplaces penetrate deeper into different markets.

The benefits of private labels are not limited to margins alone. Ecommerce companies often leverage the data gathered over the years to fill the demand-supply gaps in their product portfolios and tap into opportunities early on in terms of product variety and price point. This hybrid strategy of focussing on both third-party and private label brands has become crucial as it also helps ensure higher consumer stickiness.

“With the expansion of any business, the path of deepening revenue lines is an obvious natural step. Private labels help expand margins on top of a funnel and channel where they (ecommerce firms) already control distribution and have clear visibility of demand,” says Kshitij Shah, principal at 3one4 Capital. Overall, margins, discounting strategies and inventory management come under direct control with private labels.

With private label brands likely to corner 50% of the retail market as the retail space opens up and matures, this can be an excellent opportunity for ecommerce players in India. Incidentally, the ecommerce market in the country accounted for 21.5 % of the organised retail market in 2019, and its share in organised retail is set to grow to around 28% by FY22.

Private labels of online marketplaces also played a crucial role in the new normal when businesses struggled to cope with supply chain disruptions caused by pandemic-induced lockdowns. For instance, after restrictions were slowly lifted on the shipping of non-essential products, the visibility of Amazon’s private labels increased and translated into higher sales. This is because many third-party brands were facing working capital and labour shortages post-lockdowns. In contrast, ecommerce players found it easier to maintain the supply chain of their private label products as they had better control over it.

“The pandemic increased overall ecommerce penetration in India, and this would have definitely aided the growth of private labels of marketplaces. I also believe the overall trust in online commerce has increased a lot. People are now more open to buying brands discovered through Instagram and Facebook,” says Rohit Krishna, general partner at WEH Ventures, a seed-stage fund focussed on the India market.

Leveraging Deeper Understanding Of The Market

Data is the biggest edge that online marketplaces have over other retailers. Consider this: Ecommerce platforms have data on total sales, conversion rate, repeat customer rate and average order value across all categories. Additionally, they have in-depth insights into customer behaviour, their purchasing habits and preferences, based on the massive data collected and analysed over the years. When it comes to private labels, they can use this data to their advantage to work out optimal pricing and acceptable quality standards. This helps them cater to price-sensitive but quality-conscious customers and thus create brand loyalty.

There are other benefits. To start with, marketing becomes more streamlined as companies understand their target audience better, thanks to the data advantage. Ecommerce players also leverage customers’ trust in their platforms and recommended products. All relevant data helps them filter the right opportunities in the market and launch more private labels across categories as and when these are required. Moreover, these companies know the best-selling categories and their competitors besides the categories, which are underserved despite demand. As a result, they can adopt a targeted approach instead of wasting their time in a crowded market. They would also know the right time to offer discounts, helped by data crunching. Add to that how they have cracked other key aspects of online selling such as logistics, storage, packaging and product innovation capacity over the years, and one will clearly understand how these factors are pushing growth in the private-label space.

“Ecommerce platforms have better control on sourcing, operations, supply chain and marketing of its private-label brands, which give them an edge over other (traditional) brands. They also capitalise on their customers’ propensity to experiment online as they are assured of easy returns and refunds,” says Shah of 3one4 Capital.

What It Means For Other Independent Sellers On Ecommerce Platforms

Much like offline retailers, which have been blamed for providing more shelf space to their brands for more profits, online players are also accused of prioritising their products over third-party brands.

Globally, there have been several complaints against Amazon about the preferential treatment towards ‘own brands’ over other independent sellers on the platform. Amazon has always said that when it makes and sells its ‘own’ products, it does not use the data/information collected from individual third-party sellers, but news reports say otherwise. There have been claims that private labels of these marketplaces are enjoying better ratings and visibility over other brands.

In 2019, Allbirds co-CEO Joey Zwillinger said that Amazon was selling shoes under its 206 Collective label that looked exactly like Allbirds’ Wool Runner shoes. But the price of Amazon’s ‘copied’ product was $45, half the price of Allbirds’ shoes.

In India, too, the Confederation of All India Traders (CAIT) has been demanding government action against Amazon and Flipkart for alleged unfair business practices and their violation of India’s FDI (foreign direct investment) policy. In 2019, the CAIT had also urged the Ministry of Commerce and Industry not to allow private labels to be sold on ecommerce marketplaces.

In December 2020, the commerce and industry ministry confirmed that the Indian government was looking to revise the ecommerce FDI rules once again. In December 2018, the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, operating under the ministry of commerce, had published the Press Note 2 (PN 2) that amended the regulations applicable to ecommerce entities with foreign direct investments.

Post that, several news reports said that PN 2 prohibits selling private-label products on these marketplaces. But the government later clarified that there was no ban on private labels and added that it did not impose any restriction on the nature of products sold via marketplaces. It is to be seen what the upcoming revisions hold for private-label play on ecommerce platforms.

“Marketplaces control the placement of products, and this is probably the most controversial edge that they might have over other third-party brands. Marketplaces have been accused of promoting their ‘own’ labels (which are, in most cases, cheaper) among ‘similar items to consider’ when a consumer is looking to buy a third-party brand,” says Krishna of WEH Ventures.

According to investors and experts, small sellers should put more effort into understanding how the algorithms of these platforms work to stay ahead in the game. In addition, brands should not rely only on marketplaces for their growth and must focus on developing other distribution channels like websites and social commerce platforms to build value and traction. “They need to continuously innovate on design and product variants to keep consumer interest alive,” says Anup Jain, managing partner at Orios Venture Partners.

Will The Rise Of Direct-To-Consumer Brands Change The Equation?

Many new and small brands hesitate to list their products with large marketplaces as they fear that big players may copy their products, collect data and launch similar private labels in direct competition. Hence, a lot of companies are adopting the direct-to-consumer (D2C) business model. With the availability of easy-to-use ecommerce software from the likes of Shopify, Magento, Ecwid and third-party logistics providers, the D2C model is getting a push towards the right direction and giving ecommerce platforms and their private labels a run for their money.

“Initially, ecommerce marketplaces were the preferred choice, especially for new brands, as these players leverage their economies of scale, wider customer reach, better distribution network, easier payment processing and better customer support. But with the rise in digitisation and social media, smaller brands can easily reach a wider audience and offer efficient deliveries and multiple payment options through tie-ups,” says Bansal of BlackSoil.

Ecommerce players face yet another challenge, that of balancing growth horizontally and vertically.

“Within each vertical, all premium brands, high-quality products and large-ticket items are focussing on building their own engagement with customers,” points out Shah of 3one4 Capital.

Horizontal growth is clearly driven by reaching more pin codes. And the ecommerce platforms have been able to do it well by leveraging their own distribution channels and partner networks. “However, consistency is a real issue here and to deliver that, they are deepening investments into building their supply chains and distribution networks. But the return on these (large) investments requires a longer time horizon and, hence, will need some patience to see results,” adds Shah.

The threat from D2C brands is real enough, and so is the fierce competition from traditional brands trying to grab a large chunk of the ecommerce market. However, the overall online pie is growing, and the private labels offered by ecommerce players can easily thrive.

According to the KPMG report mentioned above, for select online apparel players, the contribution of sales from private labels could go up to 40% by 2022 from 25% in 2019. For select grocery retailers, sales could reach 45%, from 40% in 2019. Given that many small brands are only present in marketplaces and even D2C brands currently depend on an omnichannel distribution, the challenge for ecommerce platforms boils down to offering unbiased treatment to third-party brands while expanding their private labels.

The post Can Private Labels Become Big Enough To Make Ecommerce Profitable In India? appeared first on Inc42 Media.

0 Comments