Foodtech unicorn Zomato, which filed a draft red herring prospectus (DRHP) with SEBI on Wednesday (April 28), said that its unit economics has improved considerably from before the pandemic to December last year. The foodtech giant is looking to raise INR 8,250 Cr ($1.1 Bn) through its initial public offering (IPO) process.

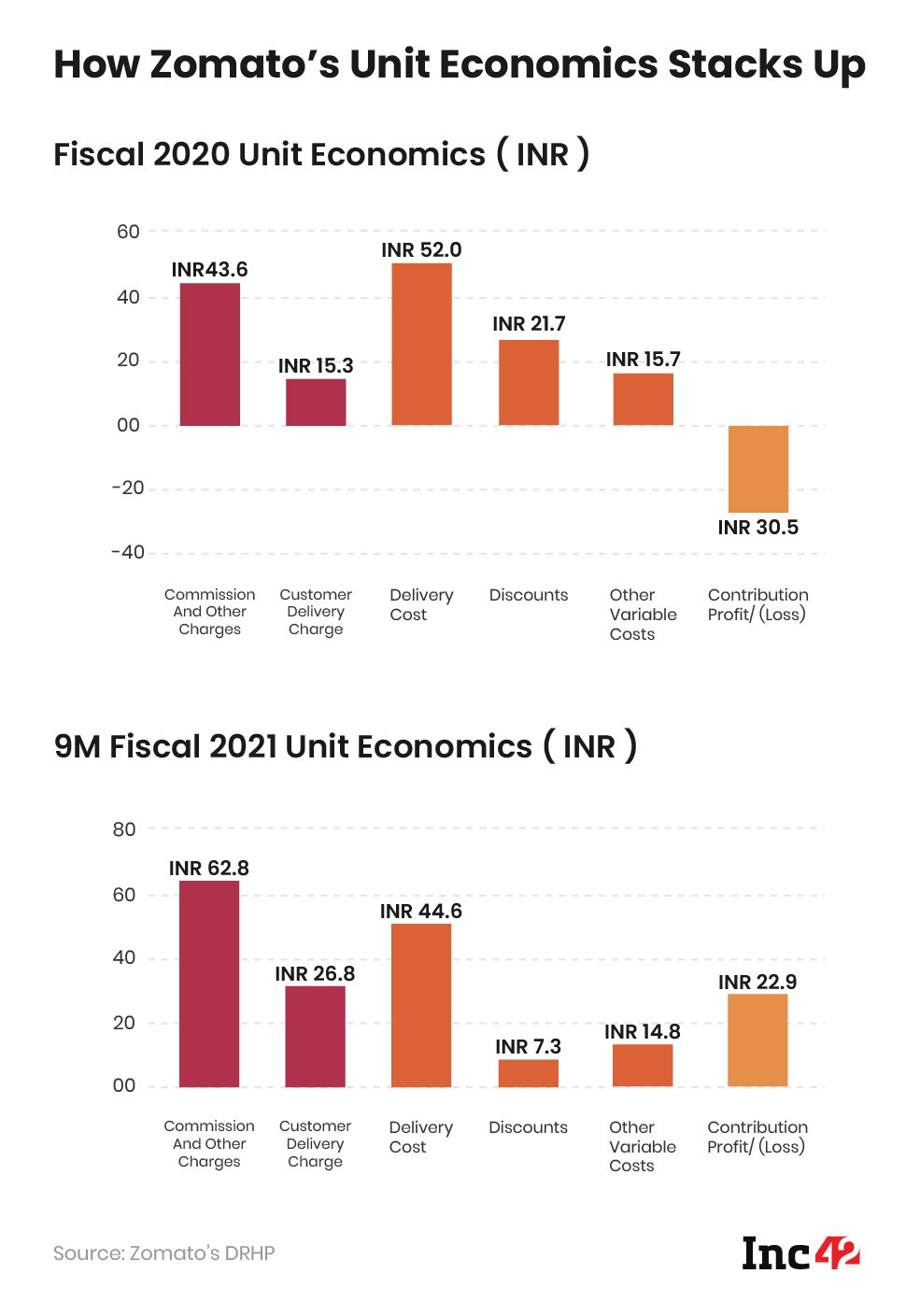

A look at the DRHP shows that Zomato achieved positive unit economics with a contribution margin of INR 22.9 per order on average from April to December 2020. This is a massive improvement from the negative INR 30.5 margin logged in FY20 (or March 2019 to March 2020), which means Zomato is actually making money per order on an average, rather than burning cash to fulfil deliveries.

One of the biggest obstacles for food delivery companies in India has been to crack the formula for positive unit economics — which means making more money than spending for an average order.

The revenue comes from charging the customer and through commissions earned from restaurants. Whereas on the spending side, variable costs such as discounts, delivery partner fees and other marketing costs come into play. When we look closer at the unit economics numbers, we can see how the company pulled off this balancing act. The company has shared numbers for FY20 (the period from April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020) and the first three quarters of FY21 (April 1, 2020 to December 31, 2020) in its IPO prospectus. Let’s take a glance at how the unit economics stacked up in these two periods:

- Commission from restaurants and ad revenues increased from INR 43.6 in FY20 to INR 62.8 till Q3 in FY21

- Delivery fees paid by customers increased from INR 15.3 in FY20 to INR 26.8 in first three quarters of FY21

- Delivery cost or money paid to delivery executives decreased from INR 52 in FY20 to INR 44.6 in FY21 till Q3

- Discounts given to users reduced from INR 21.7 in FY20 to INR 14.8 in first three quarters of FY21

Zomato reigned in spending through fewer discounts, lower payouts to delivery executives and increasing its commission from restaurants to bolster the unit economics further. Interestingly, even as the company seems to have tightened the spending, the gross order value on the platform hit an all-time high of INR 2,981 Cr in Q3FY21. This is 7% higher compared to the same period in FY20 when the GOV was INR 2,785.2 Cr.

“The company has been able to attract customers organically, thereby reducing their customer acquisition costs such as discounts and marketing, which has been a major source of cash burn in the past years’. They have also managed to improve their average-order-value per customer, increased onboarding of new partners both on the restaurant and delivery side, and brought in efficiencies in their logistics costs. All the measures, along with tailwinds due to extended lockdown has certainly helped in continued efforts in improving unit economics and path to profitability,” said Ankur Pahwa, a partner at management consulting firm EY.

The gross order value, also known as gross merchandise value in or GMV in other sectors, includes the sum of all transacted orders — deductions as a result of cancellations, returns, sales costs or discounts are not taken into consideration in this figure. As such it is not equivalent to operating revenue.

However, there is one more important point to note: the unit economics calculation shown by Zomato doesn’t include marketing and advertising spends — something that all consumer tech companies plonk huge amounts of money into. On this front, too, the company claims to have improved as ad and marketing spend was 22.44% of its total income in the first three quarters of FY21 as compared to 48.80% in FY20.

Foodtech Sector Grapples With Unit Economics

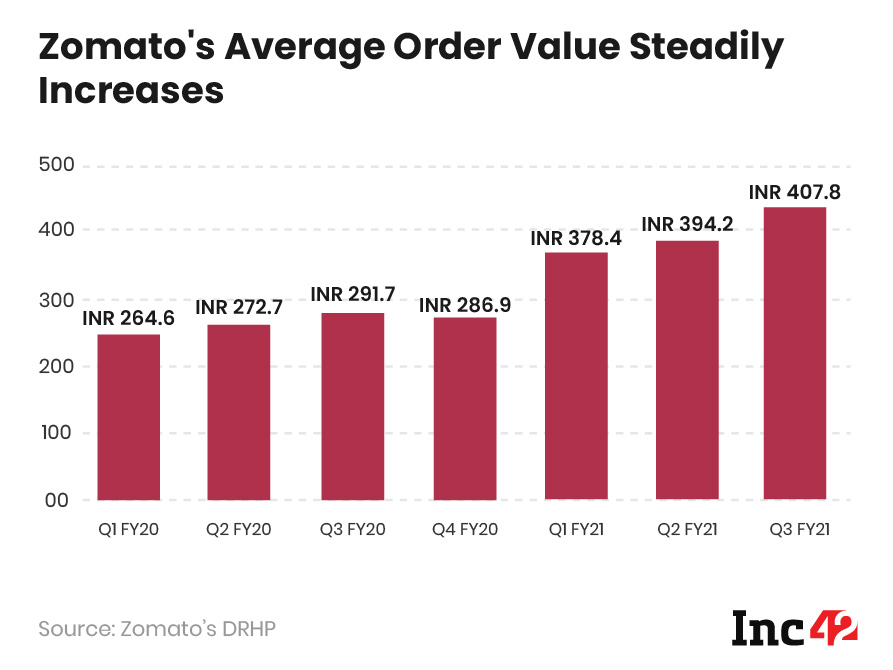

Currently, the average order value in food delivery hovers around INR 400, which has increased significantly compared to pre-Covid era, according to an HSBC report. But due to high delivery cost and expenses incurred on discounts and marketing, profitable growth is still doubtful.

“Food delivery companies are exploring the option of maximising returns from their fixed investments. Given the thin margins on food deliveries, cloud kitchens do possess great potential to become a huge margin booster. (However) going forward, it is crucial that food companies understand the complexity of operations and work on core levers to drive efficiencies whilst ensuring safe, on-time and a quality experience in deliveries. Every foodtech startup wants to put their strategy into reality. The ones which will succeed are the ones which have the consumers at the centre of their strategy,” said Harsha Razdan, partner and head, consumer markets and internet business, KPMG India.

Zomato’s average order value (AOV) has shot up 54.11% in seven quarters — from INR 264.6 in the April-June period of 2020 to INR 407.8 in the October-December quarter of 2020, according to its DRHP. AOV is a function of the price of food at restaurants and the number of people the food is being ordered for. Everything else being equal, the AOVs are higher for orders from premium restaurants.

Also, the number of orders on Zomato has grown from 30.6 Mn for FY18 to 403.1 Mn for FY20. Meanwhile, the gross order value has increased from INR 13,341.4 Mn in FY18 to ₹112,209.0 Mn in FY20.

But with a second wave of Covid cases hitting India hard, the supply of delivery workers is a challenge for Zomato, Swiggy and Dunzo. As the migrant workforce has begun travelling back home fearing another lockdown, there could be unforeseen expenses for these companies.

Although it is difficult to predict when food delivery companies may turn profits, the success story of ecommerce giants Flipkart and Amazon shows some promise. After burning through nearly $6.1 Bn in investor money between 2007 and 2018, Flipkart not only built a large ecommerce consumer base, but also a sophisticated supply chain operation that trickles down to the last-mile. With coverage in more than 600 cities, food delivery startups including Swiggy, Zomato, and Dunzo are now looking to replicate the same ecommerce journey but at a hyperlocal level.

The two survivors of the foodtech story in India — Swiggy and Zomato — now find themselves in a less competitive market, but with very little scope for improved monetisation in food delivery. So the next five years for foodtech in India will be about how players revamp themselves, reimagine their models and utilise their last-mile network to capture a bigger piece of the pie.

The post Zomato Posts Positive Unit Economics As It Files For An IPO appeared first on Inc42 Media.

0 Comments