The Amazon of India. The Uber of India. The Airbnb of India.

More often than not, the country’s star startups have been defined by their American parallels. But as Zomato’s top brass presented the foodtech company to analysts and prospective retail investors ahead of an INR 9,375 Cr public listing, they struggled to find a foodtech company elsewhere in the world that operates in the same verticals.

Although the company’s mainstay is food delivery, it has a finger in every pie related to food. Here is a quick list: A table booking service for dining in, a subscription programme called Zomato Pro giving users deals and discounts on dine-in and delivery, a private label in the health and dietary supplements space and the Hyperpure platform, mainly supplying groceries to restaurants.

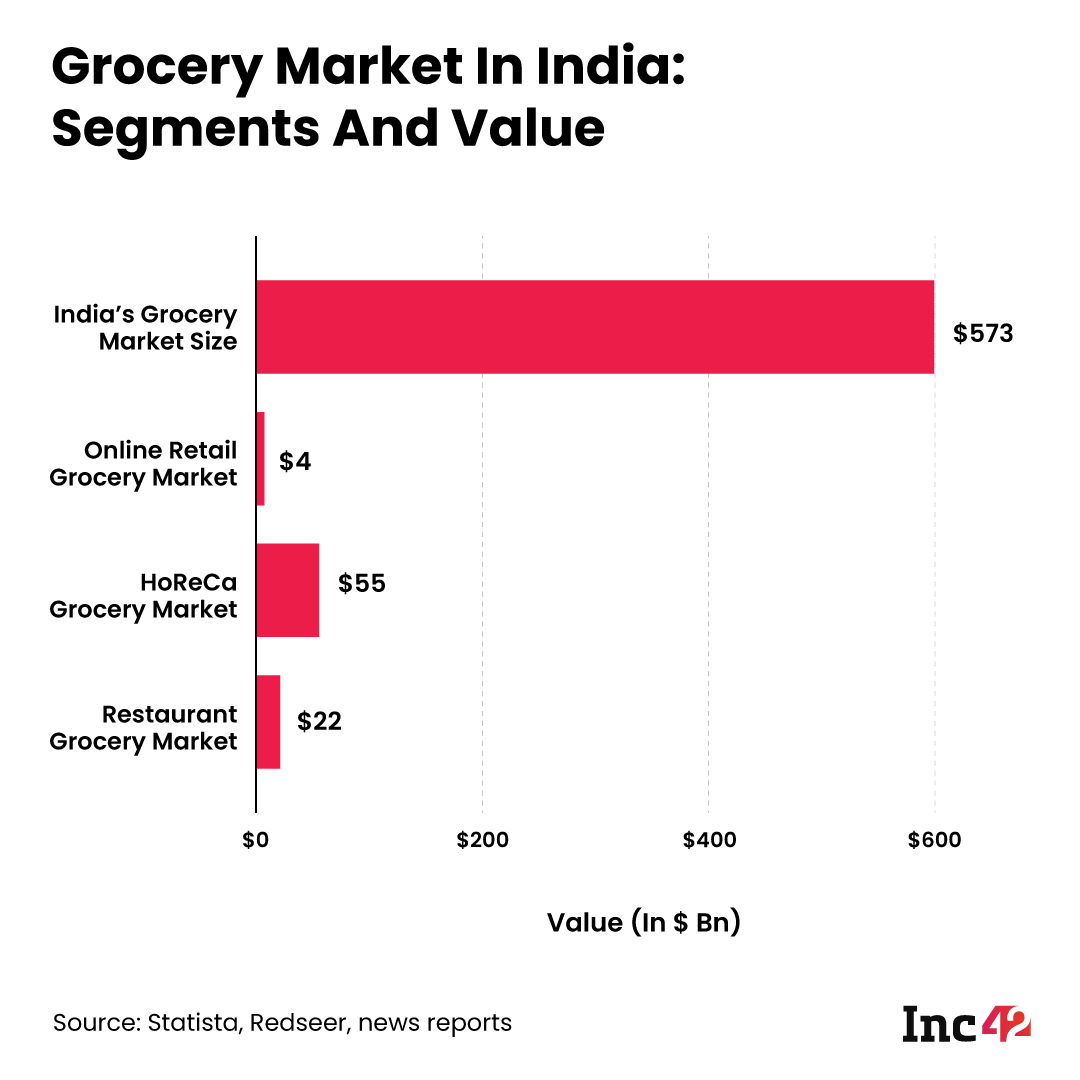

Interestingly, Zomato is looking to re-enter the online grocery market after abandoning it last June following stiff competition from the likes of BigBasket. But its interest in the approximately $573 Bn space was hardly a secret after the unicorn made a $100 Mn investment in the Gurugram-based online grocery delivery platform Grofers last month. The company has revealed its plans only recently and hopes to give the vertical a big push post the IPO. “The investment will help us get a better understanding of the grocery space and collaborate with Grofers, although at an arm’s length. Besides, there are synergies possible between B2C and B2B grocery delivery,” said cofounder Gaurav Gupta in an analyst call.

Given the convenience and the safety needed in a pandemic-hit world, home-delivering groceries is a business pursued by tech companies of all hues. The Ambanis and the Tatas of the world find it a lucrative opportunity even though making a sizable profit (or any profit, for that matter) is difficult in this space. But supplying groceries only to restaurants (part of the hotel-restaurant-café or HoReCa supplies but more niche) is unheard of even in the startup land where people claim to have unique ideas all the time and declare themselves first movers in excessively niche spaces. (For instance, an entrepreneur claimed in a Clubhouse chat room recently that he was building India’s first online delivery service of grains ground with a specific technique).

Launched in April 2019 amid much fanfare, Hyperpure has not been able to ‘move fast and break things’ — the survival mantra of tech companies. Zomato announced that the restaurant supply arm would expand to 20 cities by the end of 2020. It had even earmarked INR 55 Cr for the mega warehouses to be set up at each location. These plans went haywire, though, when the black swan event came along. As the Covid-19 pandemic struck the country in early 2020, the ensuing lockdowns forced the parent company to delay Hyperpure’s expansion. Currently, it is present in just six cities. However, all is not doom and gloom as the catastrophe has seemingly driven the adoption of this model.

When restaurants started reopening in June 2020 after the first wave, several suppliers demanded to be paid their pre-Covid dues before accepting new orders and wanted advance payments for fresh supplies. But Covid-battered restaurateurs wanted to hold on to their trickling cash flow after witnessing zero business for months and anticipating an uncertain future. In search of a viable alternative, a lot of restaurants started ordering their supplies from Hyperpure.

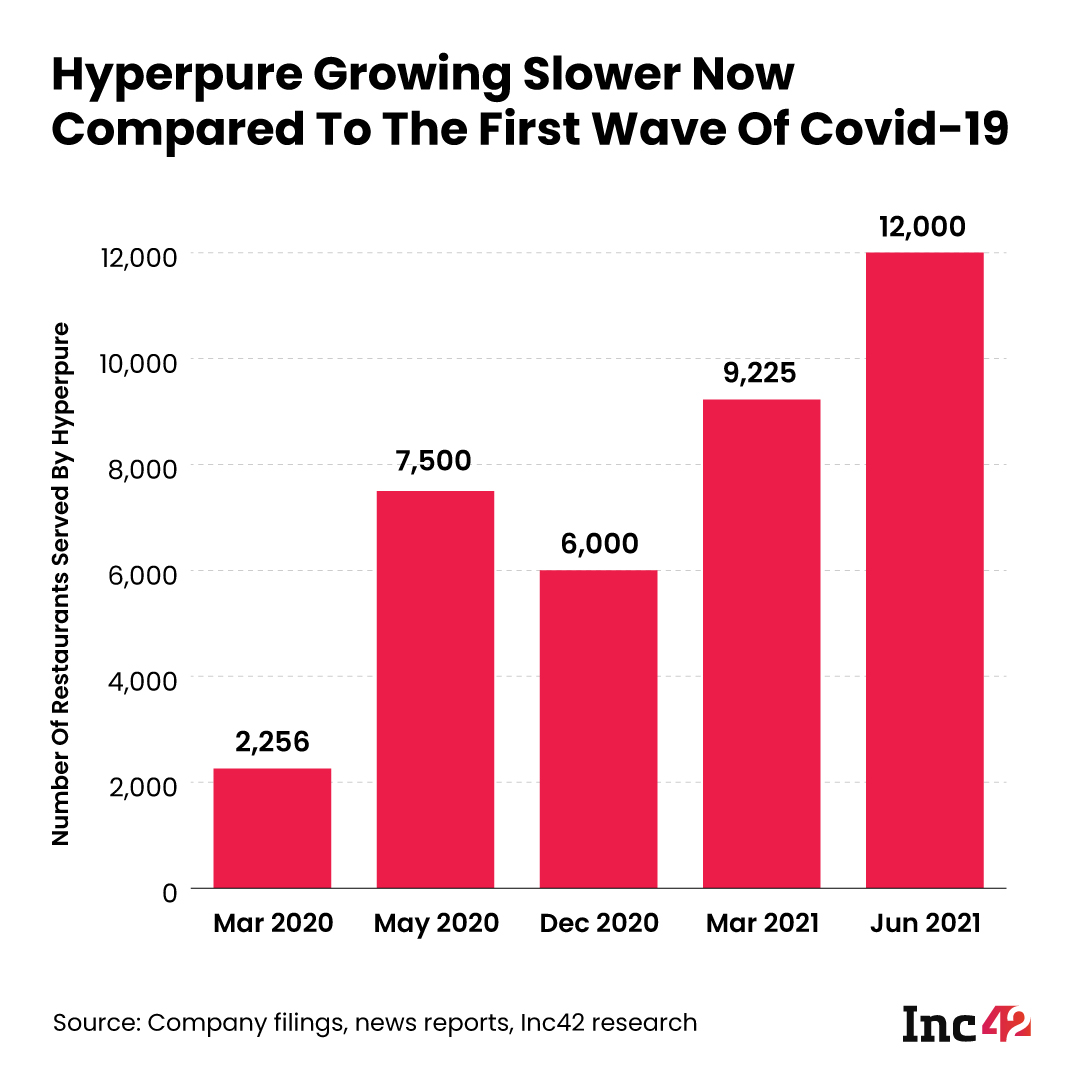

The platform saw a massive uptake in the next few months — from 2,256 restaurants in March 2020 to around 7,500 in May that year, a 232% jump. But that phase of hypergrowth seems to be over now. Requesting anonymity, a Zomato executive told Inc42 that around 12,000 restaurants were serviced in May this year compared to 9,225 units in March when the second wave started. Given last year’s growth, it is quite clear that the second wave of the pandemic could not accelerate Hyperpure’s business as before. But why did that happen?

Credit Creates A Collision Course

After the initial rush to sign up for the Hyperpure service last year, many restaurants pulled back for a couple of reasons. To start with, many of them had made up with their long-time vendors and negotiated that their pre-Covid dues would be paid in a staggered manner as business recovered.

Moreover, small restaurants function differently when it comes to procurement. Unlike their upmarket peers who order in bulk from leading vendors, these eateries prefer to source ingredients from multiple vendors as it helps them get competitive rates and rotate credit. So, many restaurants that procure from Hyperpure do so only in parts or tend to order infrequently. This lack of loyalty towards one vendor convinced Kushang, the cofounder and CEO of the Noida-based B2B grocery marketplace Supplynote (it connects vendors and restaurants), to pull the plug on the supply business.

“We were doing a million dollars of GMV and had around 2,000 restaurant customers. But we were only getting a part of those restaurants’ procurement wallets. Any midsize restaurant will require around 200 ingredients that it procures from 60-70 vendors on a rotation basis, depending on their rates. That is why we ditched Adurcup (the platform that solely supplied to restaurants) and started Supplynote,” he says.

Of course, Zomato cannot do much about a restaurant’s choice to work with multiple vendors, but it has also made a misstep on the credit front.

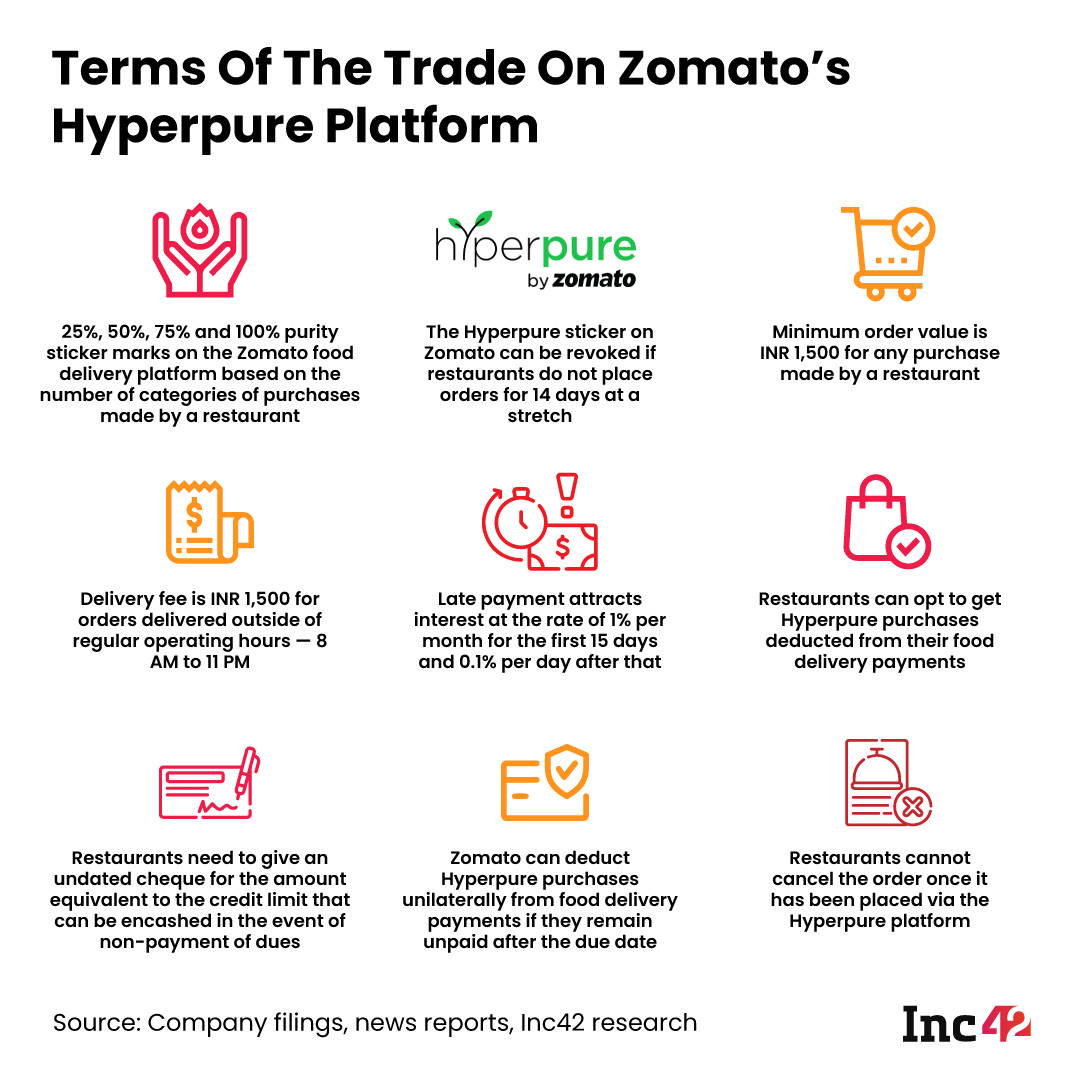

The terms and conditions of Hyperpure include a clause that says Zomato can deduct from a restaurant’s earnings on the food delivery side if dues for Hyperpure purchases are not paid on time. Many restaurants find it unpalatable, especially as credit terms with local vendors can be extended up to 60 days without interest, while Zomato levies a high rate.

When timely payment on Hyperpure purchases does not happen (the credit period may vary from 7 to 45 days), the company charges a monthly interest rate of 1% on the due amount for the first 15 days. After that, it charges a 0.1% daily interest (from the date the invoice became due) until debt closure.

Commenting on the payment structure, a restaurant owner from Whitefield, Bengaluru, told Inc42, “I don’t use Hyperpure anymore as it looks like a debt trap. First, you pay a 20% commission on food orders. Then it stops the payment on the delivery side for dues on the Hyperpure side and also charges interest on the amount due.” Delivery side payment refers to the money Zomato collects from consumers on its food delivery platform on behalf of the restaurants.

However, the foodtech company does not view it as a problem. A Zomato executive, who does not want to be named, says that the company sees the system as a feature rather than an issue. “This process solves the problem of long payment cycles in the sector and reduces a restaurant’s bandwidth spent on tallying and making payments for procurements,” he says (more on that later).

Zomato did not respond to our queries on its credit policy and other aspects such as the traction enjoyed by its Hyperpure business.

According to a Delhi-based restaurant chain owner, “The supply chain was shattered last year, and we were not sure whether suppliers followed the no-touch protocol. So, we started sourcing raw materials from Hyperpure. But at the end of the day, we don’t want to become dependent on another company, be it Zomato or Swiggy.”

Perils Of A Niche Market

That restaurants do not want to rely too much on a corporate supply chain is only part of why restaurant grocery suppliers in the organised space have witnessed muted growth. In truth, no player has really focussed on this segment as it is very small compared to the overall B2B grocery market.

Interestingly, Swiggy started a grocery delivery service for restaurants called Stan Plus amid the first wave of the pandemic last year. But it did not take off from the beta stage. A few restaurants Inc42 spoke with said that they did not continue with Stan Plus due to late and spoiled deliveries. Metro Cash & Carry and BigBasket’s HoReCa arms also supply to restaurants, but do not have a service exclusively built to cater to the segment.

This is how industry executives analyse the current market value. In FY20, total revenue from restaurants in India was around INR 4.08 Lakh Cr or $54 Bn. Now, a restaurant’s food cost is roughly 40% of its revenue, which means the restaurant sector’s overall grocery procurement in FY20 could be less than INR 1.6 Lakh Cr or $21.6 Bn. This is hardly a significant sum considering that the overall grocery market in India, valued at $573 Bn in the same period, was 27 times bigger.

It is now pretty clear why organised players in the wholesale grocery space — namely, Metro Cash & Carry, Ninjacart, Amazon, Flipkart and Udaan — have zeroed in on supplying kirana stores that account for a big chunk of the $573 Bn market.

Unlike the wholesale grocery players that cater to restaurants as part of the bigger HoReCa segment, Hyperpure is a unique platform because of its strict niche operations, the nature of its competition and the way it is trying to resolve some of the pain points faced by restaurants.

For Hyperpure, the real competition comes from the unorganised sector, local traders and mandis, to be precise, accounting for 91% of the total grocery procurement by restaurants, according to Kushang of Supplynote. So, the question is: What can Zomato do to disrupt the unorganised sector in spite of its cost disadvantages?

“At many restaurants, procurement is done by chefs or purchasing managers who take a commission from suppliers, and the money is siphoned from the amount invoiced,” says Rahul Singh, founder and CEO of The Beer Café, a fast-growing beer-and-food chain. Therefore, Hyperpure is a boon to owners like him, who have to manage multiple outlets and are flooded with hundreds of procurement bills to be audited and cleared every month.

However, chains like The Beer Café only account for around 8% of the 7 Mn estimated restaurants in India (nearly 56K outlets). Also, many of these include multinational brands like McDonald’s, Burger King, Pizza Hut and more, which have specific ingredient requirements for differentiation and continuity of taste and flavours, considered to be consumers’ top preferences. As a result, these brands cannot switch from one supplier to another all too often for better pricing or other benefits.

“I procure things like butter and ketchup from Hyperpure. But my biggest ingredient is processed chicken that comes from Godrej Tyson, while fresh vegetables like onion and lettuce are procured from mandis in Nashik (Maharashtra),” says Kabir Jeet Singh, cofounder and CEO of Burger Singh, a listed restaurant chain.

The quality and taste of major ingredients are important factors for restaurant brands, and they do not like to chop and change the sourcing under normal circumstances.

There is yet another restriction on Hyperpure’s total addressable market (TAM), although Zomato itself has put it there. The company only caters to FSSAI-certified restaurants, and there are just 1.83 Lakh of them in India. The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) is the regulatory body that gives licences to run different types of food businesses in India. Any food outlet without a licence is operating illegally.

Unit Economics Is The Keystone

For Hyperpure, the biggest challenge is maintaining healthy unit economics, unlike the unorganised players with low-profit margins. Singh of Beer Café is not overly optimistic, though. “Its TAM could be as big as INR 30,000 Cr, but there is hardly any money to be made on a per-order basis as Zomato sells at the current market price. I don’t think one can have a comfortable margin in this business.”

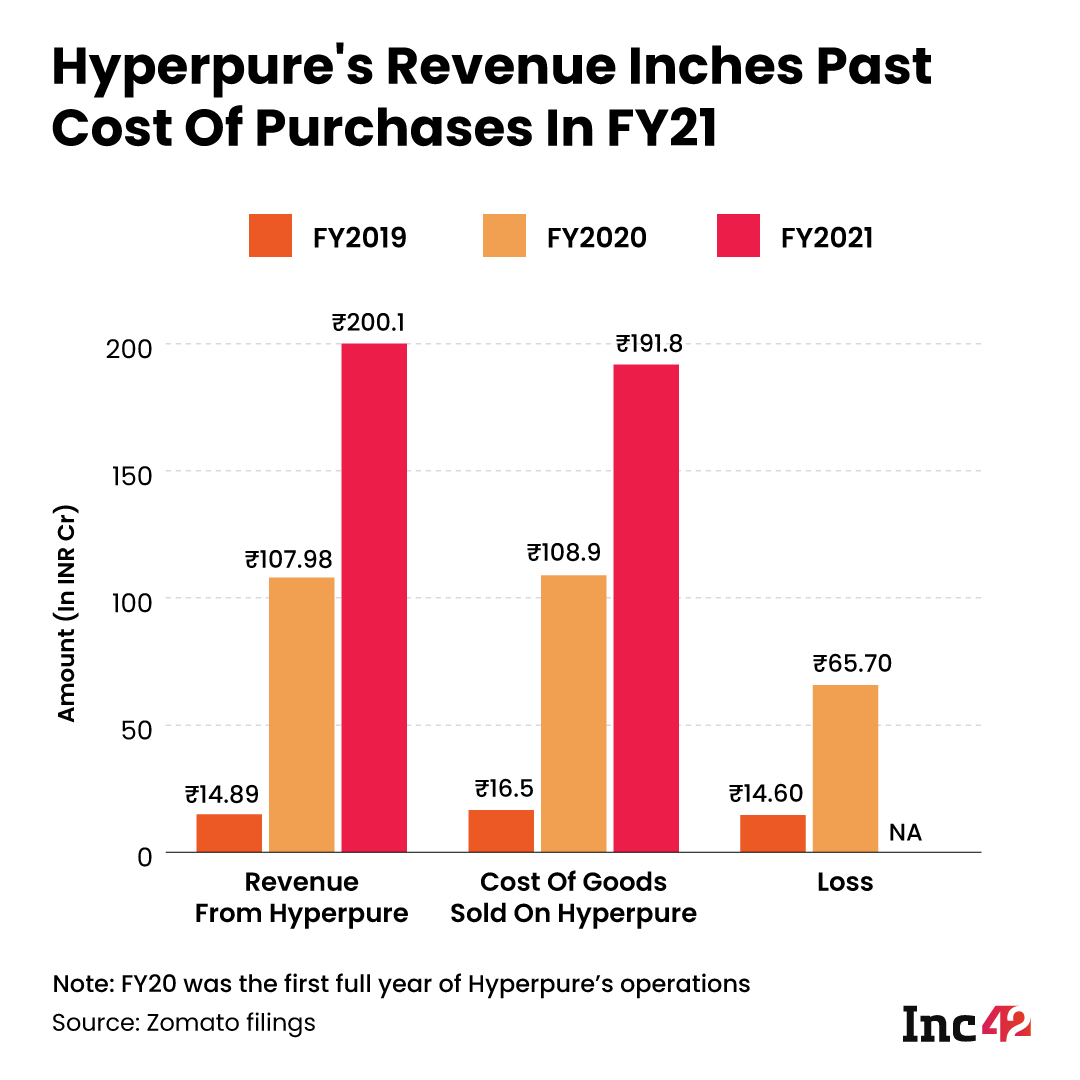

Contrary to his observation, Hyperpure seems to be making money on a per-order basis. It bought supplies worth INR 108 Cr and sold the fare to restaurants for INR 110.5 Cr but incurred a net loss of INR 65.7 Cr in FY20, according to company financials.

This is not surprising as the cost of building and running a supply chain weighs heavily on such businesses. Of course, investing in warehouses and technology is part of the fixed cost, but the bigger and more troubling piece is the variable cost of making the delivery.

“Out of this loss, around INR 25 Cr came under fixed costs, another major chunk was the cost of fulfilment, and the rest was on account of discounts, which is a smaller cost comparatively,” says a top executive at a management consulting firm that has worked for Zomato.

According to him, order fulfilment (last-mile delivery) accounts for 10-12% of the total cost of operations, and it may go up to 15% due to wastage. It also goes up when a company delivers fish, poultry or similar items that require a better-than-average cold chain solution. That is why players like Ninjacart, Amazon and Flipkart only deliver staples, vegetables and fruits where the average cost per kg ranges between INR 30 and INR 45. In contrast, Hyperpure’s average cost is INR 80-85 per kg, while the cost of fulfilment is INR 8-10 per kg.

Interestingly, the cost part does not work in the same way for small, unorganised players. For instance, they often overload their delivery vehicles three to four times the original capacity. But Zomato or other players in the organised sector cannot do it for fear of getting embroiled in safety and other legal issues. Again, vehicle utilisation is higher for unorganised players as they operate in common markets and can pick up several ready-to-dispatch orders from suppliers at one go. All these make the delivery cost of Hyperpure four or five times higher than the mandi sellers and local traders. As it is, the business takes a hit every time it sells at current market rates.

In spite of these cost issues, an analyst at a VC firm that has invested in Zomato says that investors are betting on Hyperpure’s 10x growth in the next two-three years. The person does not want to be quoted, though, as he is not authorised to speak to the media.

One way for Hyperpure to increase its earnings is betting against the market rate of a commodity. The trick is to buy groceries from farmers and manufacturers at a fixed price for a certain period but sell to restaurants at market prices. This way, it can benefit whenever the market price increases.

For the first two years of its operations, Hyperpure’s cost of goods was more than the revenues it earned. But this changed in FY21 as it incurred a cost of INR 191.8 Cr on purchase of stocks and clocked sales worth INR 200.1 Cr.

However, given the niche nature of the business and the ‘debt’ worries of restaurateurs, that kind of scaling up may not be possible unless the company resorts to deep discounting. Disruption in food delivery was easy for Zomato and its ilk as they created a new distribution channel, and there was no competition present in the old economy. However, grocery supply to restaurants is a substitution business as merchants have been doing it since restaurants have existed.

Besides, the biggest challenge will be to convince restaurants that there will be no arm-twisting in this space. On July 5, the National Restaurant Association of India (NRAI) complained to the Competition Commission of India (CCI) that the anti-competitive practices of the Zomato-Swiggy duopoly were hurting them. While the restaurant body has been fighting foodtech giants for a long time over deep discounting, private labels and the policy of not sharing customer data, the latest grouse is all about vertical integration.

Simply put, vertical integration may happen when a business seeks to control the entire value chain within a segment (food, in this case). Tech companies worldwide have started to realise that monopolising distribution is not enough for ecommerce marketplaces to corner massive profit margins. In fact, the secret of value extraction lies in two broad strategies: They can become a supplier themselves (through private labels) on the marketplace and sell more value-added services to ‘product creators’.

The first is no longer viable in India as lax regulations are catching up. The country’s ecommerce and FDI policies have thrown a spanner in the works, and marketplaces selling their private labels are facing too many hurdles right now. So, companies like Zomato are looking to tap into other areas of the value chain to make money.

Even if it does not become successful, Hyperpure’s journey will have essential lessons on the vagaries of verticalisation and how these may impact the country’s tech businesses and investors. Most importantly, it will test the ability of a consumer tech company to replicate its playbook in the B2B space, a strategy that is increasingly becoming the norm as unicorn startups look for puddles of profitability in their expansive loss-making businesses.

The post Inside Zomato’s Hyperpure: The Battle To Control India’s $54 Bn Restaurant Economy appeared first on Inc42 Media.

0 Comments