The food delivery battle is heating up once again. Almost a year after a nationwide lockdown put consumer internet businesses in a tight spot, food delivery startups Swiggy, Zomato, and even Dunzo are preparing to raise large amounts of capital.

Gurugram-based Zomato has been gearing up for an IPO at a whopping $8 Bn valuation for a while now and has already mopped-up $250 Mn in equity financing last month. On the other hand, Bengaluru-based Swiggy is closing in on an $800 Mn in funding from a clutch of new investors, in what seems to be a race to build a $1 Bn chest to take on its IPO-bound rival. Smaller but no less ambitious hyperlocal delivery startup Dunzo has also hit the market to raise $150 Mn in financing from new investors.

Foodtech Isn’t A Winner-Takes-All Market In India

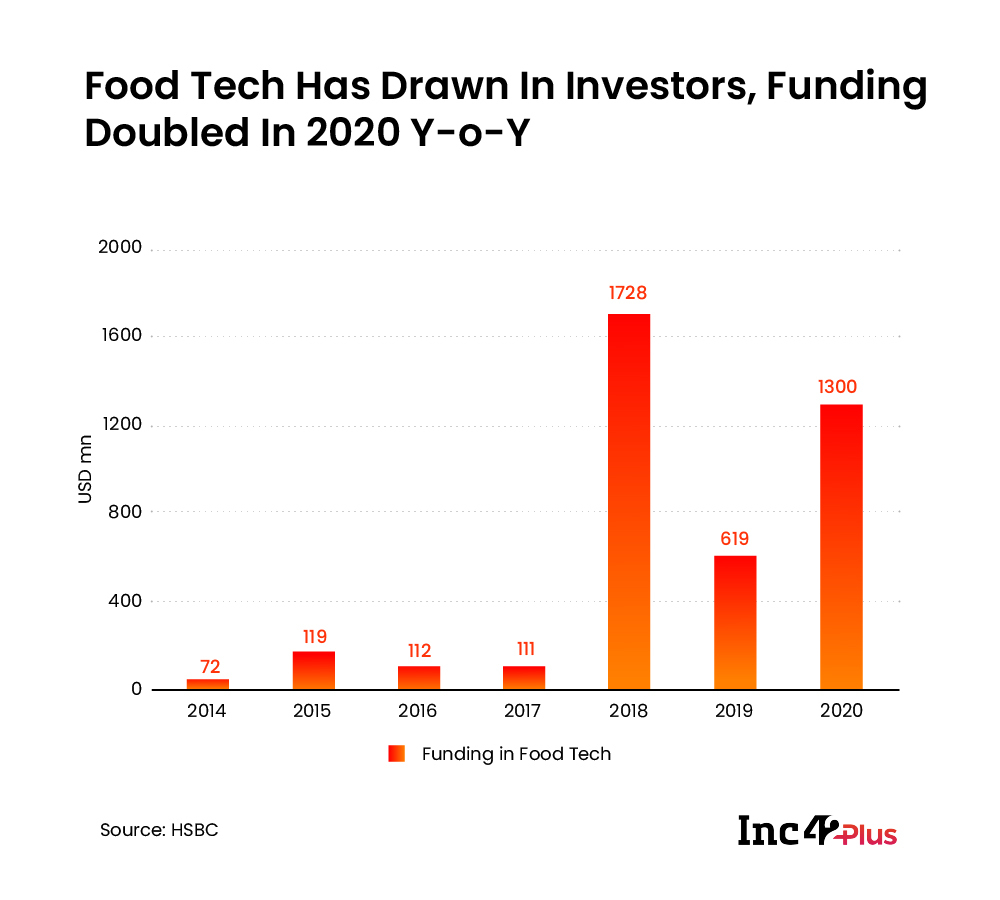

With several casualties such as TinyOwl, Foodpanda, Spoonjoy, and even UberEats (which exited to Zomato) in the past, the Indian food delivery market continues to be a tough nut to crack. Yet investors betting on the food delivery market are not surprised. According to a report by market research firm HSBC Global Research, venture capital and private equity funding into Indian food delivery and foodtech startups has been growing steadily since 2014, and there are no signs of a slowdown.

A majority of funding in food delivery is concentrated on Swiggy and Zomato, which prompts analysts and investors to suggest that the Indian foodtech market is effectively a duopoly. But as seen in recent developments, Swiggy and Zomato have latched onto divergent business strategies.

“We think (that) food delivery industry has attained a decent equilibrium now in terms of competition and is basically a duopoly market. There’s little reason for Swiggy to significantly undercut Zomato. This follows the global pattern with 2-3 players enjoying healthy growth,” a February 2021 HSBC report on India’s consumer internet market says. The report also poitned out that fodotech currently handles annual GMV worth $2.5-3Bn in 2021, with an opportunity to cross $16Bn in annualized GMV by 2025.

So, for many experts and analysts, the big question is whether the Indian foodtech market has the potential to generate more billion-dollar startups? This is where Dunzo comes in because a duopoly perhaps is not up to the task of serving the varying needs and demands of a multicultural nation.

Zomato’s Full-Stack Play

While Zomato and Swiggy are considered food delivery rivals, their philosophies and growth paths are totally different — and Dunzo is coming from an even disparate place. Although the genesis of these companies can be traced back to food delivery, the next few years of foodtech is India is not going to be focused just on food alone as we will see.

Zomato, which originally launched in 2008 as a restaurant discovery platform that aggregated information such as menus, dishes, and user reviews, did not get into food delivery until 2015. In fact, in FY20, Zomato’s primary revenue source included ad sales, food delivery, ordering and Zomato Pro subscriptions. For its next leg of growth, Zomato is now doubling down as a direct service provider for restaurants by offering online discovery, tablebooking, cloud kitchen infrastructure and B2B raw material supply for restaurants. It has even indicated the desire to enter food-adjacent categories such as grocery — which it eventually shelved — and now nutraceuticals and health supplements.

And some of these bets are paying off. For example, in FY20, the company’s B2B restaurant supplies subsidiary ‘Hyperpure’ recorded eightfold growth in revenue which grew from $1.8 Mn in FY19 to $14.7 Mn in FY20. At present, more than 2,280 restaurants use Hyperpure, Zomato claims. These carry the ‘Hyperpure’ tag on the Zomato app, which tries to showcase Hyperpure as a trust metric.

Hyperpure not only allows Zomato to better forecast demand and therefore source raw materials such as grains, fruits and vegetables on a larger scale, but it’s also an upsell to its restaurant partners — part of the bundle of services aligned with food delivery. Hyperpure also widens the addressable market for Zomato considerably, given that India currently has 70 Lakh restaurants and the bigger market opportunity comes from the 2.3 Cr restaurants in the unorganised segment, according to FHRAI’s estimates.

However, experts point out that Zomato positioning itself as a full-stack service provider to restaurants is still an undercooked pitch.

Sidu Ponnappa, SVP engineering at Gojek India, says that from a clientele point of view, the B2B supply model for restaurants is better suited for smaller and fragmented restaurants rather than established and branded chain restaurants who prefer having control over their own supply and procurement process. This may not be great for Zomato in terms of the scalability of this vertical.

“A large restaurant will eventually want to have its supply chain for sourcing fresh raw materials. And even if B2B startups want to cater to big restaurants you are talking about setting up a massive supply chain and logistics on top of perishable goods. This is a tough business unless you are narrowly focusing on certain raw material SKUs only. Zomato may have to elevate its operations to near ecommerce level of complexity to have wide coverage,” adds Ponnappa.

While Zomato is going for a full-stack approach, rivals Swiggy and Dunzo are taking the ‘super app’ model, borrowed from apps like Gojek, Postmates, Grab and Instacart. Built on top of highly efficient last-mile logistics operations, food delivery is just one of the categories in a super app. This model has seen some success globally in Southeast Asia and the US, but Swiggy and Dunzo are not exactly going by the template set by Gojek and the likes.

Swiggy, Dunzo Narrow Focus To Hyperlocal

A typical super app in the delivery and commerce space offers everything from food delivery, ride-sharing, movie and travel ticketing, home services, payments, lifestyle services and more. But Swiggy and Dunno have narrowed their focus on hyperlocal deliveries, by either aggregating stores (marketplace model) or using dark stores (inventory model). That’s because food delivery alone will not add to future revenues for Swiggy and Dunzo, given their specific focus on deliveries and not on the supply side of things like Zomato.

Even Zomato had briefly entered the grocery delivery space by aggregating stores on its app during the initial lockdown period in April last year, only to pull the plug on the service two months later.

Swiggy also originally entered grocery using a marketplace model in September 2019 under the ‘Swiggy Stores’ branding only to shut down the entire model a year later. Swiggy currently operates grocery delivery only in two cities including Gurugram and Bengaluru under the Instamart name. Instamart is essentially an adaptation of BigBasket’s dark stores model, with a major differentiation in delivery frequency. While Bigbasket takes somewhere between four to 48 hours to fulfil orders, Swiggy aims to deliver groceries in less than 45 minutes. Swiggy is achieving this model using a network of dark stores branded as ‘Urban Kirana’.

Typically speaking, in the hyperlocal deliveries ecosystem, any store within the hyperlocal geography eventually becomes a point of supply for the platform. In a way, Swiggy and Dunzo will compete with ecommerce marketplaces such as Flipkart, Amazon and even Jio Mart and Tata’s upcoming super app. There will be some overlap given the omnichannel nature of ecommerce marketplaces as well. But hyperlocal deliveries are fundamentally different from the more widespread distribution architecture of an ecommerce marketplace, since goods (food, meat, grocery, etc) are locally procured, supply is monitored in real-time and last-mile fulfilment has to begin near-instantaneously after an order is placed.

Two sources aware of Swiggy’s operations told Inc42 that food delivery will make up around 75%-80% of the startup’s revenue even if the company launches non-food categories in all 600+ serviceable locations, and this is unlikely to change for the next few years. This inflexibility is largely due to the challenge for hyperlocal delivery startups to smoothen procurement and add equal depth to supply for all categories such as grocery, pet foods, meat, and alcohol in Tier 3/4 cities and smaller towns. Dark stories are a fix for that.

With the marketplace supply being low in smaller towns and certain locations even in large cities, Swiggy and Dunzo have been expanding their inventory play through dark stores. But this doesn’t mean that both startups may want to fully move to an inventory model, like BigBasket and Grofers are looking to do, but rather find a fine balance.

Swiggy’s Instamart currently stocks a total of around 1,000 most ordered SKUs across its dark stores, sources said. But with a lower SKU count, the average order value (AOV) is much lower than that of Grofers and BigBasket where the AOV is above INR 1,000. This is in fact why both Swiggy and Dunzo charge hefty delivery fees on non-food orders.

“When Swiggy operates its own dark store, it has the capability to get 15% margins on every order (average) which is similar to a small kirana or a supermarket. But the challenge is that Instamart orders have an additional cost as capex for managing the physical store itself, and the cost of paying salary to ground staff managing the store. So roughly, a store that stocks 800-1,000 SKUs can break even at INR 50 Lakh GMV sales per month,” added another source aware of Swiggy’s operations.

In the effort to meet this target, and to boost margins, both Swiggy and Dunzo are likely to launch private labels for the bestselling categories, sources close to both companies said. However, in response to Inc42’s queries, Swiggy said that it doesn’t have any plans to venture into private labels. Dunzo did not respond to an email seeking queries until the publishing of this story.

“Instamart is currently under pilot in two cities (Bengaluru and Gurugram) and our focus is on scaling the business and fine-tuning the offering through our partnerships with FMCG brands. We do not have any private brands on Instamart,” the company’s spokesperson said.

Zomato and Swiggy had totally different origins and Dunzo is also a different breed. But it is interesting how food delivery and hyperlocal delivery have become so closely linked in the wake of the pandemic. If a startup can do one well, it can also look at expanding into the other.

These startups are navigating different paths primarily because there is pressure to make units profitable — particularly for Zomato and Swiggy — according to a venture capitalist who has invested in hyperlocal delivery firms. The investor asked not to be named as they did not want to comment on rivals publicly.

“There is pressure to make the unit economics work and (hyperlocal) startups have moved on from just those experiments with cloud kitchens. Zomato is doing more backward integration of food itself, Dunzo is probably going to get into more active dark stores, and I won’t be surprised if Dunzo also starts doing a bit of private labels to shore up margins,” said the investor.

The Way Forward Amidst A Second Wave

Estimates from HSBC Global Research shows that China’s food delivery volumes currently are above 40Mn orders a day, which does provide some indication of actual market opportunity for hyperlocal delivery startups in India. But food is unlikely to get Indian startups to these volumes, given the cultural differences between China and India. Indian food delivery and hyperlocal startups have no option but to diversify their offerings

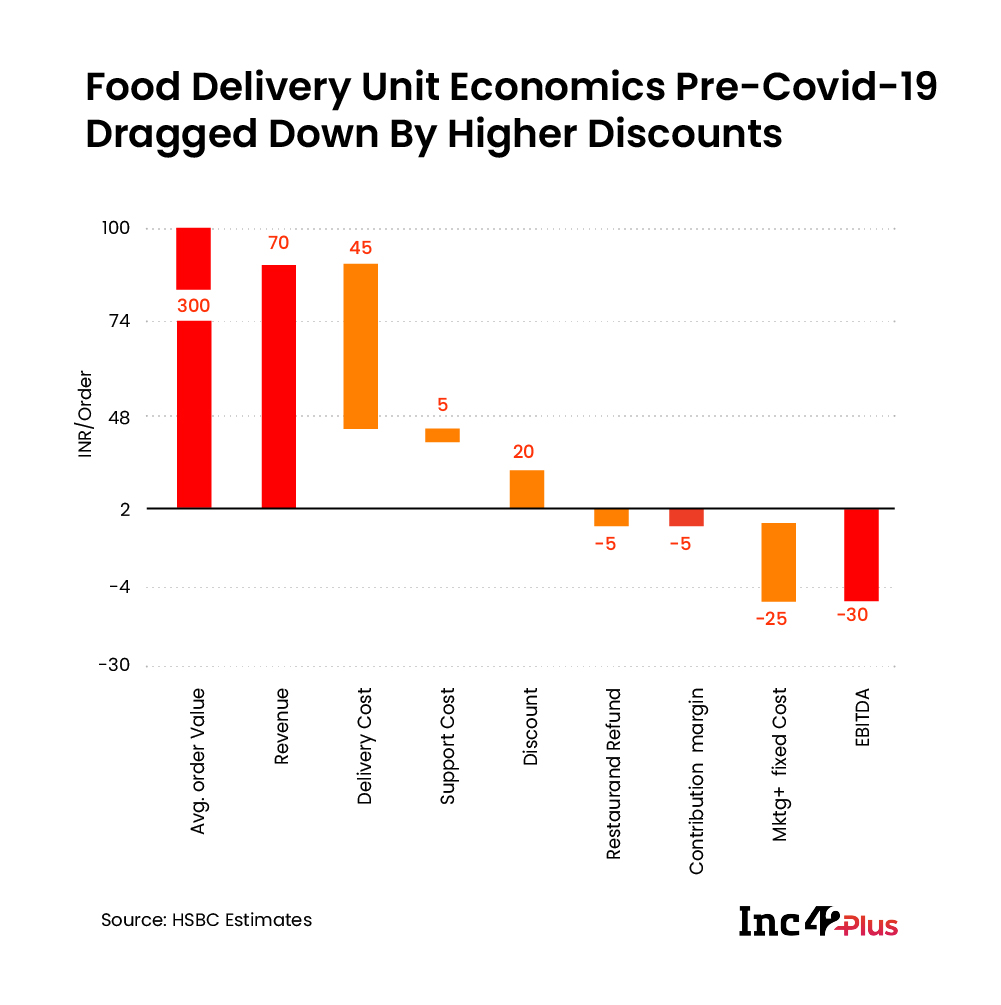

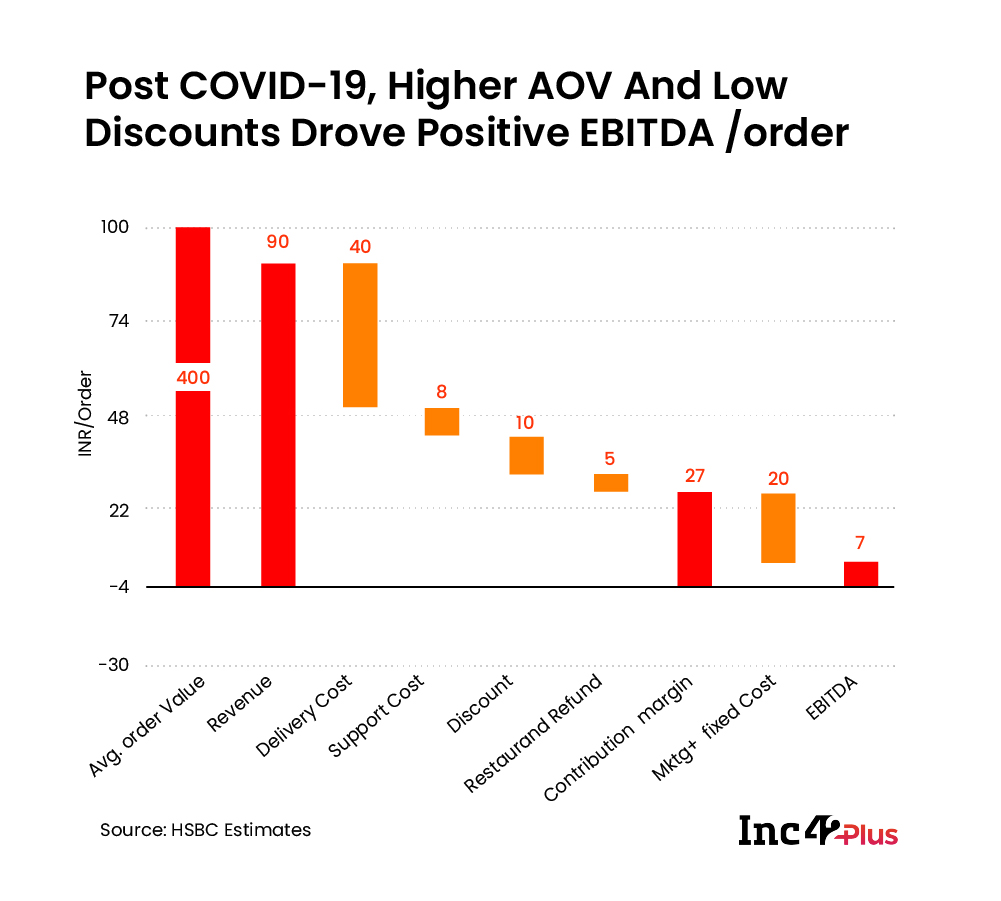

Currently, the AoV in food delivery hovers around Rs 400, which has increased significantly compared to pre-Covid era, according to HSBC. But due to high delivery cost and expenses incurred on discounts and marketing, profitable growth is still doubtful.

“Food delivery companies are exploring the option of maximising returns from their fixed investments. Given the thin margins on food deliveries, cloud kitchens do possess great potential to become a huge margin booster. (However) going forward, it is crucial that food companies understand the complexity of operations and work on core levers to drive efficiencies whilst ensuring safe, on-time and a quality experience in deliveries. Every foodtech startup wants to put their strategy into reality. The ones which will succeed are the ones which have the consumers at the centre of their strategy,” said Harsha Razdan, partner and head, consumer markets and internet business, KPMG India.

But with a second wave of Covid cases hitting India hard, the supply of delivery workers is a challenge for Zomato, Swiggy and Dunzo. As the migrant workforce has begun travelling back home fearing another lockdown, there could be unforeseen expenses for these companies.

Although it is difficult to predict when food delivery companies may turn profits, the success story of ecommerce giants Flipkart and Amazon shows some promise. After burning through nearly $6.1 Bn in investor money between 2007 and 2018, Flipkart not only built a large ecommerce consumer base, but also a sophisticated supply chain operation that trickles down to the last-mile. With coverage in more than 600 cities, food delivery startups including Swiggy, Zomato, and Dunzo are now looking to replicate the same ecommerce journey but at a hyperlocal level.

The two survivors of the foodtech story in India — Swiggy and Zomato — now find themselves in a less competitive market, but with very little scope for improved monetisation in food delivery. So the next five years for foodtech in India will be about how players revamp themselves, reimagine their models and utilise their last-mile network to capture a bigger piece of the pie.

The post The Future For Indian Foodtech Giants Swiggy And Zomato Is Not Just About Food Delivery appeared first on Inc42 Media.

0 Comments